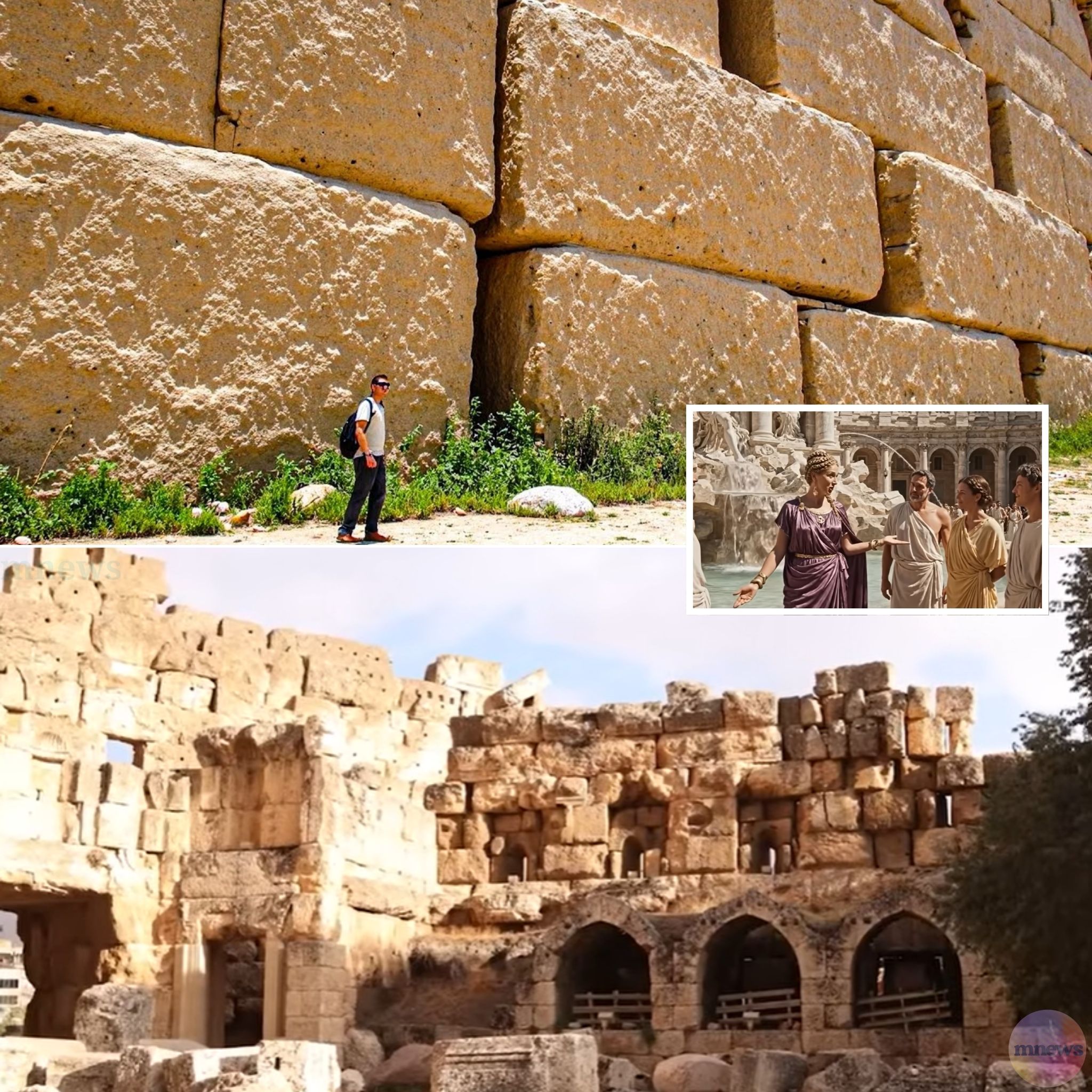

BAALBEK, LEBANON – A monumental archaeological and engineering mystery, one that has baffled experts for centuries, may finally have been unraveled. The colossal megalithic stones at the ancient site of Baalbek, some weighing an astonishing 1,500 tons, stand as a testament to a sophistication that predates the Romans by millennia, forcing a dramatic rewrite of ancient history.

New archaeological evidence confirms the site’s foundational stones are far older than the Roman temples that crown them. Excavations have uncovered pottery with cuneiform writing and Neolithic artifacts, proving human occupation stretches back nearly 11,000 years. This discovery shatters the long-held belief that the Romans were the original architects of the site’s most impossible features.

The scale of construction defies modern understanding. The famed Trilithon—three limestone blocks each weighing approximately 900 tons—is perched 23 feet in the air with millimeter precision. Nearby quarries hold even larger monoliths, like the 1,500-ton “Forgotten Stone.” Contemporary engineering struggles to explain its movement and placement.

“Our most powerful cranes today can barely lift 20% of that weight,” noted one engineer analyzing the site. The Romans, renowned for documenting their engineering feats, left no record of constructing these foundational blocks. Their complete silence is now seen as a critical clue that they inherited the site.

“This silence is deafening,” explained a historian familiar with the research. “It strongly suggests these stones were already there when the Romans arrived. They built their magnificent temples on top of a pre-existing, megalithic foundation whose origins were already lost to time.”

The breakthrough follows decades of international investigation, including major excavations by the German Archaeological Institute. Researchers discovered that ancient builders expertly quarried the megaliths by cutting along natural rock fissures, a technique also seen in later Roman projects. More startlingly, the construction techniques match those of Herodian architecture in Jerusalem, hinting at a shared, advanced knowledge.

While the Romans undoubtedly constructed the iconic temples above, the identity of the original megalith builders points to a far older civilization, possibly from the Phoenician or even earlier periods. This civilization possessed engineering knowledge so advanced it has remained elusive, fueling theories of lost technologies.

The implications are profound. Baalbek is no longer just a Roman relic but a palimpsest of human history, with its deepest layer representing an achievement that challenges our entire timeline of ancient technological capability. This isn’t merely about how they moved the stones, but why such a monumental effort was undertaken over five thousand years ago.

The site continues to be a focal point for archaeologists, with each layer of soil removed revealing more questions than answers. The solution to Baalbek’s greatest mystery confirms one staggering fact: a highly advanced, organized society with monumental capabilities flourished in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley long before the dawn of classical antiquity.