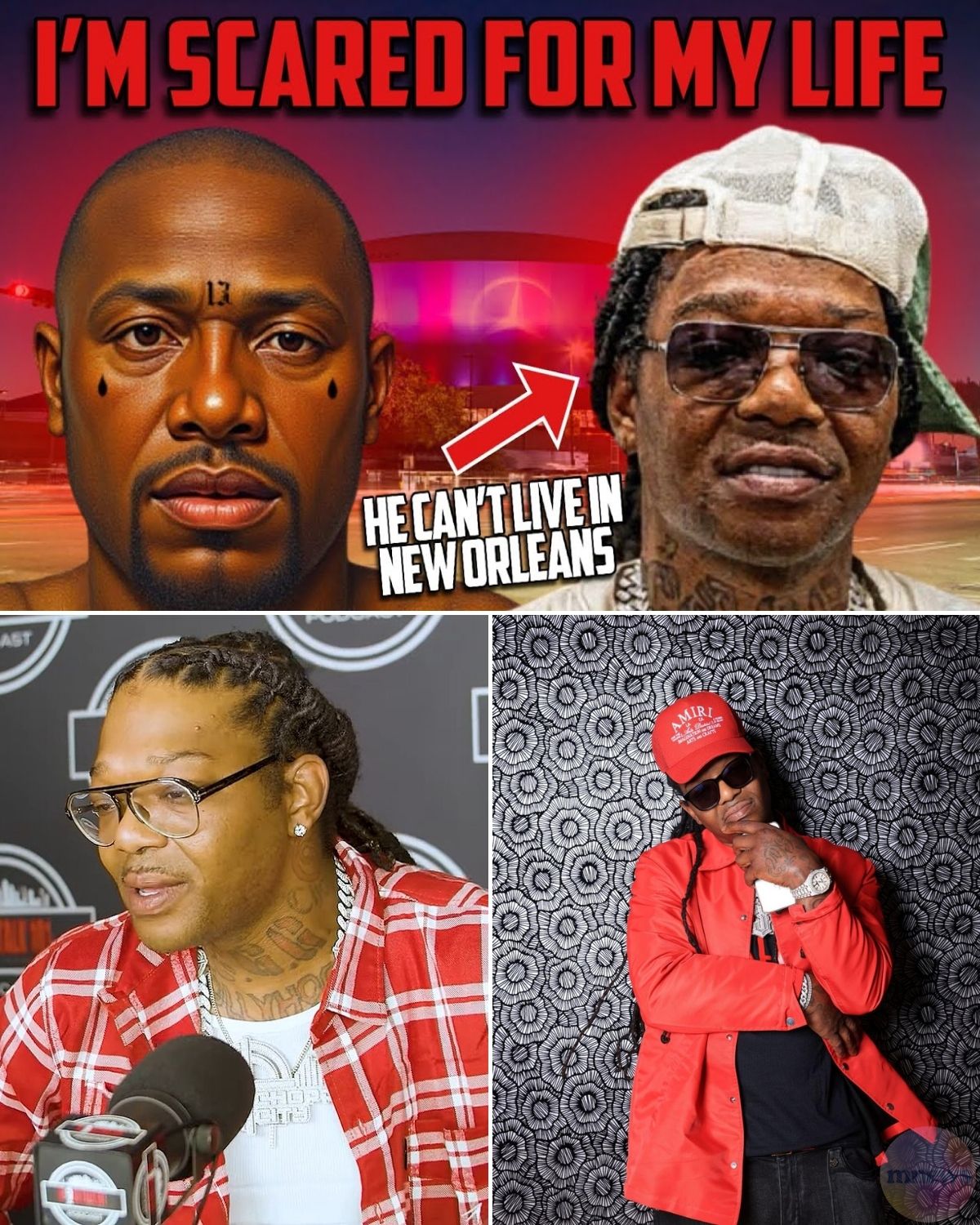

A former Cash Money Records star has publicly declared his fear of returning to his hometown, citing a specific and formidable threat from the streets of New Orleans.

In a recent, emotionally charged interview, Christopher “BG” Dorsey, a foundational figure in the city’s hip-hop history, stated he cannot safely return to New Orleans. His reason points directly to the perilous legacy of past associations and the enduring danger of street politics.

“I felt like my life was in jeopardy,” BG stated, his voice laden with palpable tension. “I felt like it wasn’t safe for me.” The artist, recently released after a lengthy prison sentence, emphasized this was not posturing but a raw assessment of survival.

The interview served as a stark message to the city he helped put on the map. Industry observers noted he “kept it 100,” avoiding bravado to speak a grim truth. “He knew he was going to get his [back] pushed back if he moved back,” one commentator summarized.

Central to this declared threat is the name Jerod “Fetty” Fedison. Their paths, emblematic of New Orleans’ dual pipeline of fame and infamy, fatally converged years ago. BG, with platinum success, and Fedison, with deep street credibility, formed an alliance that seemed potent.

That partnership was shattered during a late-night traffic stop. Police found illegal firearms in the vehicle, leading to arrests for both men. The legal aftermath would define Fedison’s trajectory and cement his notorious reputation.

Facing severe federal time, Fedison was presented with a choice: cooperate or disappear into decades of incarceration. He chose to testify, first in his own case and later as a pivotal witness in a landmark murder trial.

His testimony helped convict Telly “Wild” Hankton, whom authorities labeled one of the city’s most dangerous criminals. A turning point, as one analyst noted, was an eyewitness—understood to be Fedison—describing the murder in brutal detail before jurors.

That decision to “flip” rewrote his legacy. In the court’s eyes, he was a cooperating witness. On the streets of Uptown and the 13th Ward, he was branded with the indelible label of a “rat,” a transgression considered unforgivable.

“Testify once, you mocked. Testified twice, you’re dead,” the narrative explains. Fedison’s name began to travel on whispers, a cautionary tale of broken codes. His reputation didn’t expire; it mutated into a permanent threat.

Despite leaving town, the past proved inescapable. Fedison was later arrested in Jefferson Parish following a violent incident involving gunfire. At 38, he found himself back in the system, now a more calculated and isolated figure.

The legal outcome was harsh but expected. More damning was the social exile. “Dudes out the 13th no longer praise Fet,” the account states. Younger generations treat him as a pariah, while old associates view him as a trophy waiting to be claimed.

BG’s public admission of fear underscores this relentless street calculus. It acknowledges that Fedison, operating from a place of having “nothing left to lose,” represents a unique and potent danger. His knowledge and his breach of protocol make him unpredictable.

This saga unfolds against a harrowing backdrop of city violence. Homicides in New Orleans have surged approximately 70% this year compared to the same period last year, with 189 murders reported, according to the Metropolitan Crime Commission.

In this climate, old scores fester, and memories are long. Fedison’s story, as noted, lacks a Hollywood ending. It is a cracked sidewalk in Central City—stepped over, but always present. He moves as a “dead man walking,” his name forever etched in street lore and court transcripts.

For BG, a legend from the city’s most famous rap dynasty, the message is clear. The fame that provided an exit cannot guarantee a safe return. The streets that raised him, now governed by a different generation’s rules and grudges, have issued a verdict he feels compelled to obey from a distance.