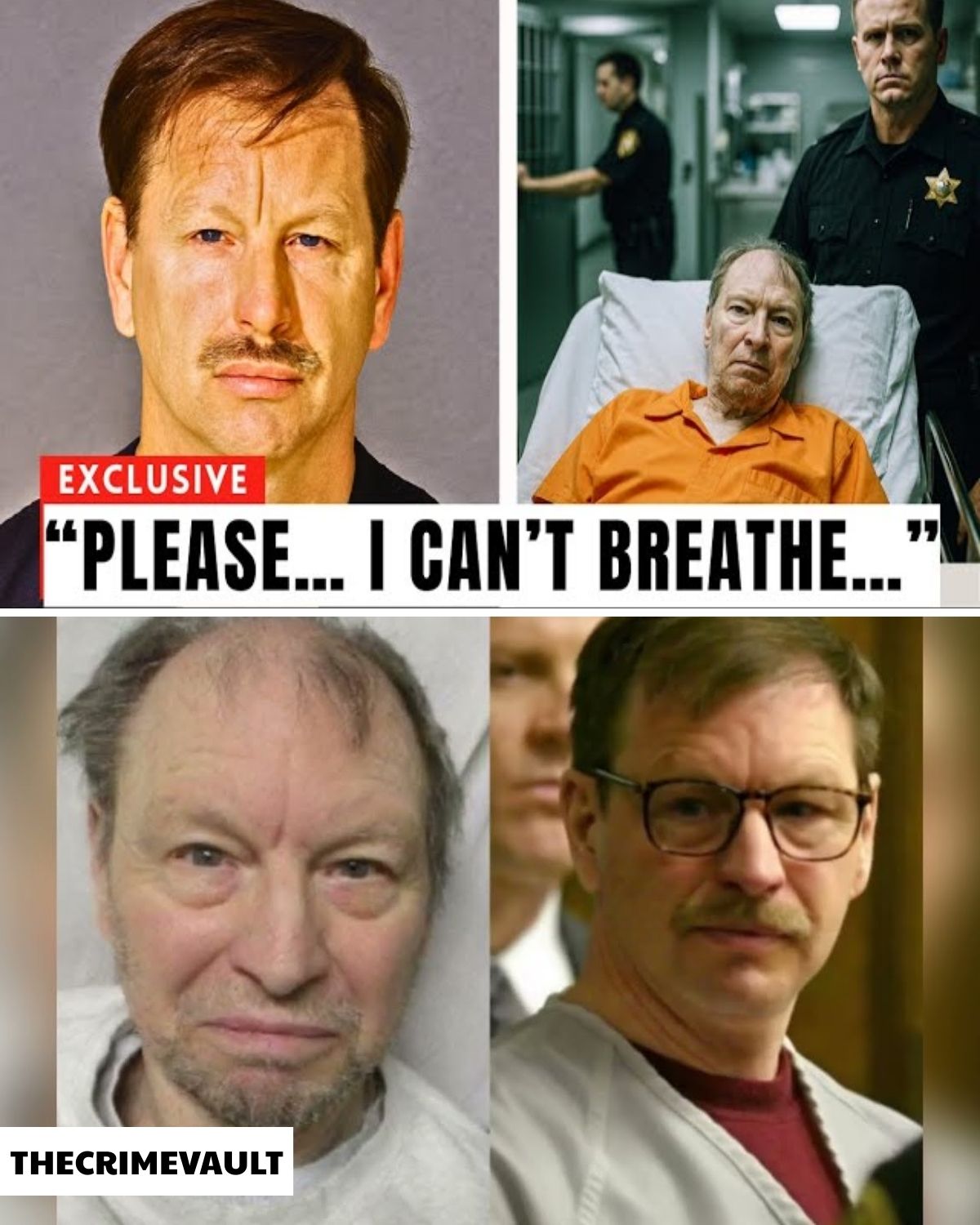

Gary Ridgway, the infamous Green River killer, known for the brutal murders of at least 49 women, is now facing the twilight of his life in a stark medical unit within the Washington State Penitentiary. The man who once evaded justice for nearly two decades now lies frail and weakened, a shadow of the predator he once was.

As of December 2025, Ridgway’s existence has been reduced to the confines of a small, sterile room. No family visits him; no friends offer comfort. Instead, he is monitored by correctional officers and medical staff, living in a reality that starkly contrasts the terror he inflicted on the Seattle area during the 1980s and 1990s.

As of December 2025, Ridgway’s existence has been reduced to the confines of a small, sterile room. No family visits him; no friends offer comfort. Instead, he is monitored by correctional officers and medical staff, living in a reality that starkly contrasts the terror he inflicted on the Seattle area during the 1980s and 1990s.

Once a figure of chilling dominance, he now struggles with the physical decline brought on by age. The same system he evaded for years is now responsible for his care, a bitter irony that underscores the complexities of justice. His slow deterioration, marked by the relentless passage of time, has become a form of punishment that many argue is worse than death.

Inside the prison’s highest security wing, Ridgway’s daily life is meticulously controlled. Every movement is monitored, every meal delivered under watchful eyes. He spends long hours alone, his world shrinking to the confines of a cell designed for maximum security. This is not solitary confinement, but it carries the weight of isolation nonetheless.

The end-of-life care he now receives is stark and clinical. The medical unit, devoid of warmth, focuses on maintaining basic comfort for inmates whose health has declined significantly. Here, the realities of aging collide with the harshness of prison life, creating an environment where dignity is scarce.

As Ridgway’s health continues to decline, he faces the consequences of his past actions in a way that many would argue is fitting. The man who once wielded control over vulnerable lives now finds himself dependent on others for even the most basic tasks. His physical limitations serve as a constant reminder of the suffering he inflicted for so long.

The moral questions surrounding his care are profound. Should a man responsible for such extensive harm receive compassionate treatment? Or does his current state reflect a justice system that refuses to become what it punishes? The debate rages on, with opinions divided on whether his current suffering is a form of justice or an unacceptable concession.

Critics of Ridgway’s plea deal, which spared him the death penalty in exchange for cooperation, argue that he escaped the ultimate punishment. Yet, others contend that a lifetime spent in confinement, aging in isolation, represents a more enduring form of accountability than a swift execution.

As the years pass, Ridgway’s condition continues to deteriorate. The stark reality of his end-of-life care raises difficult questions about the responsibilities of the justice system. The cost of providing long-term medical care to someone with such a dark legacy is a burden that taxpayers may bear, igniting further debate about the ethics of his treatment.

This situation forces society to grapple with the complexities of punishment, accountability, and human rights. Ridgway’s case serves as a chilling reminder of how the consequences of one’s actions can reverberate far beyond the courtroom, leaving a lasting impact on families and communities.

In the end, as Gary Ridgway faces his final days, the question remains: is the slow, isolated decline he endures a punishment worse than death? Or should justice have taken a different path? The answers may lie in the perspectives of those who have suffered the most from his heinous acts.