A seismic discovery within the ancient monasteries of Ethiopia threatens to upend two millennia of Christian tradition and scriptural understanding. New attention on a sacred, guarded canon reveals teachings of Jesus Christ allegedly spoken in the forty days following his resurrection, texts absent from the Bibles used by most of the world’s churches.

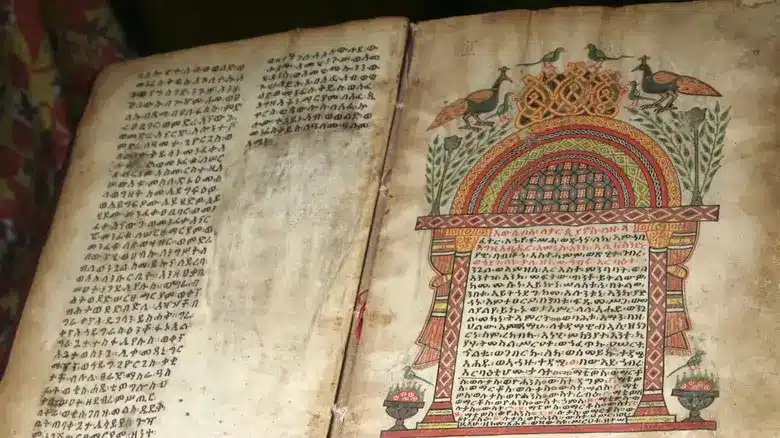

For centuries, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has preserved a scriptural canon of 88 books, written in the sacred liturgical language of Ge’ez. This stands in stark contrast to the 66-book canon established in the West. Among these texts is the “Book of the Covenant,” which church tradition holds contains the direct, post-resurrection dialogues of Jesus with his disciples.

These teachings, meticulously hand-copied by generations of monks in remote highland monasteries, present a radically different spiritual focus. They emphasize an internal, direct connection with the divine, challenging the need for institutional intermediaries. “You build temples of stone and gold, but the true temple is within you,” one passage recounts Jesus saying, according to these traditions.

The survival of these texts is attributed to Ethiopia’s unique historical path. The nation embraced Christianity in the 4th century and, protected by geography, never attended the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. That Roman-led council was instrumental in standardizing the biblical canon for the empire, selecting texts that supported a centralized church hierarchy.

Ethiopian theologians assert that mystical writings emphasizing personal revelation and spiritual freedom were systematically excluded by Rome. The Ethiopian canon, however, retained these works, including the Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees, alongside the newly highlighted post-resurrection accounts.

Scholars examining the tradition report these “hidden words” contain profound prophecies and warnings. The texts allegedly record Jesus cautioning against future corruption, where his name would be shouted by empty hearts and towering churches would forget the simplicity of love. He purportedly blessed “the quiet believers whose faith needs no audience.”

One of the most striking elements within the broader Ethiopian tradition is a narrative found in what some call the “Gospel of Peace.” This text, as described by church historians, presents a non-crucifixion story, suggesting Jesus withdrew to the wilderness to continue teaching about healing and harmony with creation. This narrative, while heretical to mainstream Christianity, is presented not as modern revisionism but as an ancient, protected strand of belief. It underscores a Jesus whose mission was to teach humanity “how to truly live,” not merely to die for its sins.

The implications of these teachings are profound. They suggest a form of Christianity that developed independently of Roman influence, one that is deeply mystical, personal, and subversive to structures of power. The idea that the divine dwells within each person potentially renders external religious control unnecessary. Ethiopia’s status as the only African nation to avoid European colonization further insulated its religious traditions. When Western missionaries arrived, they encountered a faith already centuries old, with its own complete and unassailable scriptural foundation.

The physical preservation of these texts is a testament to devotion. For generations, monks in monasteries like those on Lake Tana or at Debre Damo have dedicated their lives to fasting, prayer, and the sacred duty of manually transcribing these words, believing they safeguard the pure voice of Christ.

Modern academia remains divided. While some historians dismiss the narratives as later traditions, others point to Ethiopia’s early conversion and the linguistic antiquity of Ge’ez as factors demanding serious scholarly investigation. The texts offer a crucial window into the diverse landscape of early Christian thought before standardization.

The teachings call for a faith expressed through action and silent integrity. “Let your silence speak louder than sermons. Let your body become a living prayer,” one teaching instructs. This reframes spirituality as a constant, embodied offering rather than a ritual performance. At the heart of the Ethiopian tradition is a prophecy of a “forgotten fire.” This is described not as apocalyptic destruction, but as a spiritual awakening that burns away pride and illusion. It is a fire said to rise from the margins, from the forgotten and the overlooked, not from established institutions.

The potential rediscovery of these teachings arrives at a time of global crisis in institutional trust and a widespread search for authentic spirituality. The message of an internal kingdom of God, accessible without hierarchy, resonates with contemporary seekers disillusioned with organized religion.

PROPHECIES, WARNINGS & A DIFFERENT KIND OF JESUS

Researchers describe these texts as containing astonishing prophecies and blistering warnings. Jesus is said to caution His disciples that:

“My name will be shouted by empty hearts.

Great churches will rise, but love will fall.”

He blesses “the quiet believers,” those whose faith needs no applause.

This is not the institutional Jesus of councils and empires—it is a Jesus who distrusts power, who calls for humility, who urges each soul to become a living sanctuary.

THE MOST CONTROVERSIAL TEXT: A GOSPEL WHERE JESUS IS NEVER CRUCIFIED

Perhaps the most shocking tradition comes from what some historians call the “Gospel of Peace.” This text presents a narrative in which Jesus does not die on a cross; instead, He withdraws into the wilderness, continuing His teachings of healing, harmony, and the sacred bond between humanity and creation.

To mainstream Christianity, this version is heresy.

To Ethiopia, it is ancient memory.

To scholars, it is a tantalizing window into early Christian diversity before Rome enforced uniformity.

This Jesus is not primarily a sacrificial figure—He is a teacher, healer, and revealer, showing humanity “how to truly live.”